Dashi is probably one of the most important elements of Japanese food. To be fair, it is one of a long list of important elements, but dashi is integral. Comprised at its most basic level of konbu (kelp), shiitake mushrooms, and/or katsuobushi flakes, dashi serves as the foundational element of any number of dishes for everyone from the home cook to the high-end chef.

What dashi brings to any dish it joins is a hearty dose of umami. The fifth dimension of taste, umami is the nearly undefinable thing that makes us want one more bite of a juicy hamburger or that hunk of cheese so irresistible. Kikunae Ikeda confirmed its existence in his laboratory in 1908, but the Ainu, one of Japan’s Indigenous peoples, were probably the first ones to really put it to use and trade it. The word, konbu, is likely a form of kompu, the Ainu word for this delectable seaweed. It shows up in third century Chinese most likely, scholars believe, as a result of trade between China and regions where the Ainu lived.

Dried konbu.

Konbu, shiitake, and dried bonito are nearly off the charts packed with umami. Drying these ingredients only serves to further concentrate their levels of umami, which makes them an ideal addition to just about any food. If you doubt, compare a sun-dried tomato to a fresh one or roast pork to a dry-cured ham.

Dried shiitake

Friends, dashi has saved my kitchen. Before Japan and before I learned hot to make dashi, my soups were more miss than hit. Some landed directly on the compost pile. After dashi, I’ve managed to consistently make soup that we savor to the last drop and aim to eat again. I’ll share below my method which combines tips learned from both Yoshimi Daido of Tokyo Kitchen while on assignment and Elizabeth Andoh of Taste of Culture during one of her classes.

Glass jar with konbu and shiitake.

Soak the konbu and shiitake.

I use the konbu and shiitake available at my local supermarket. Andoh provides terrific explanations of the different varieties of konbu as well as shiitake in Kansha, which familiarized me with both of these ingredients. I use an old jar to do the soaking, as I saw Andoh do during class, which is remarkably convenient as it doesn’t tie up a bowl or pan and makes it easy to tuck away while you do other tasks.

A few hours later, the konbu has stretched, and the shiitake expanded.

Pour the konbu, shiitake, and their water into a saucepan.

Swirl a bit of extra water in the jar to catch any last bits of residue and add it to the pan. (HT to Elizabeth Andoh for this one.) As you become more experienced, you also learn how much water to swirl to bring the dashi up to the right amount for the dish you have in mind.

Bubbles around the rim mean it’s time to turn off the heat.

Put the lid on and start the heat. Turn off the heat when a ring of bubbles forms around the edge of dashi.

For Daido, this was the signal that the dashi was thoroughly heated. Dashi, I remember her saying, should never be boiled as it would ruin the flavor.

At this point, some would throw in a handful of katsuobushi flakes, but I do not. Pre-Covid, we hosted a number of people for dinner, and more often than not the crowd included a vegan or vegetarian. I have simply kept this habit.

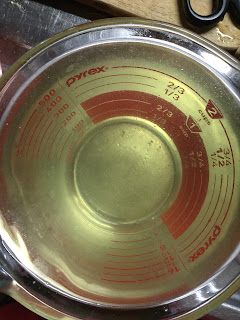

Two cups of dashi at the ready!

Strain the dashi.

It is possible to immediately strain it into a soup pot, but it is also perfectly fine to set it to the side while going about other foodly activities. I have done both with great success. I have even stored it in the refrigerator for a night. I have accidentally (ahem) kept it longer, but as someone who seems to get food poisoning at the drop of a spoon, I didn’t use it.

Post-dashi konbu and shiitake.

What to do with the konbu and shiitake?

Well, there are uses for those. The shiitake can be cut up and added to the soup or tossed in with rice. Andoh has a great recipe for tsukudani, a type of rice topping made from the konbu that is out of this world, in Washoku.

Forgive me, Friends, but I have also used the konbu to great effect in my garden as a compost. I know there are plenty who will wince at this, but it seemed a better option than tossing them when I didn’t have time to make tsukudani or just forgot about the container of konbu in the refrigerator a few days too many.

Other Forms of Dashi

Before I landed in Yoshimi Daido and Elizabeth Andoh’s kitchens, I used bottled dashi. It made good soup, and we were happy. Then, someone pointed out that it is often mostly sugar and other things that were not so delectable. I tried granules, but for me, they didn’t result in the kind of flavor I wanted. Making it from scratch did give me the flavor I wanted, and so I’ve never looked back. Yes, it does require a tiny bit of pre-planning, but a short soak can be fine, and it only takes a few moments for that ring of bubbles to appear. You’ll be glad you made the effort.

Other Reading

Konbu (Kelp) from the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research is part of an excellent series on Japanese food and heirloom varieties.

Finding extraordinary konbu in a remote Hokkaido fishing village at The Japan Times is an excellent window into the tradition of growing, harvesting, and drying.

Dashi 101: A Guide to the Umami-Rich Japanese Stock at Serious Eats is an excellent overview of dashi, its ingredients, and methods.

The Umami Information Center lets you look up various foods and check their umami levels!

Kansha: Celebrating Japan’s Vegan and Vegetarian Traditions by Elizabeth Andoh has a terrific section on Stocks that includes konbu dashi as well as others.

Seaweed: A Global History by Kaori O’Connor goes beyond konbu (kelp) to explore this most traditional of foods. I haven’t read it yet, but it is on my desk just waiting to be opened!

Ise Tsuyoshi: The Little Book of Dashi is a sweet little tome by Yuuki Tanaka, a dashi-obsessed chef.